The Positive Side of Hacking: Innovation Through Curiosity

The term “hacking” often evokes images of digital mischief or breaches, but not all hacking is destructive. In fact, a great deal of hacking is rooted in creativity, curiosity, and a drive to improve. When I refer to hacking here, I mean “lifehacking”—the art of repurposing and reimagining rather than breaking. Many of us, myself included, have been hackers from a young age, constantly exploring and experimenting with everyday objects.

For instance, who hasn’t taken apart a functioning alarm clock, only to find it near impossible to reassemble? Yet, those springs and gears have launched many budding inventors’ projects, becoming components for Meccano builds or homemade experiments.

Lifehackers have long found value in adapting existing tools for new purposes. Trevor Baylis, for example, created the clockwork radio by combining a wind-up mechanism with a dynamo and radio. None of these elements were new, but together they created a device that didn’t require batteries—ideal for raising awareness of health issues in developing regions. When we see such transformative ideas, it’s natural to think, “Why didn’t I think of that?”

Online searches reveal an array of creative, practical, and occasionally humorous hacks, like the use of an old Apple computer case as a mailbox, transforming the phrase “let’s check my inbox” into a literal experience.

One concern I have today is that with our increasing reliance on ready-made products, we often discard items that stop working, instead of exploring how they work or could be repurposed. Especially with younger generations, the spirit of inquiry that encourages us to “hack” everyday items is less emphasized, yet it’s essential for fostering creativity and resilience.

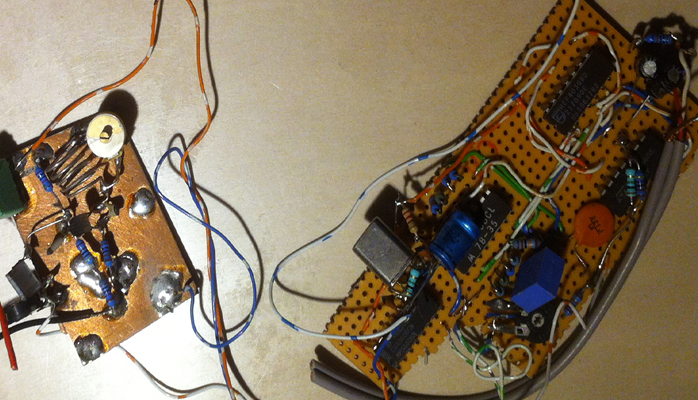

Even in the realms of electronics and computing, hacking can lead to technological advancements. In my early career, colleagues found that failed EPROMs (a type of early computer memory) could serve as makeshift coffee cup warmers when powered up—albeit not in the intended way! Such hacks may seem whimsical, but they foreshadowed developments in thermoelectric technology. Of course, I don’t necessarily recommend experimenting in unsafe ways, as these projects can carry risks.

Interestingly, crystal radio kits have made a comeback, offering people a hands-on look at how early radios worked. I remember building my own with household materials—an empty jar, aluminum foil, wire, and a germanium diode. Even older enthusiasts may recall using lead crystal and gramophone needles rather than a “sophisticated” diode.

Looking forward, the Raspberry Pi project has sparked a new wave of ingenuity, providing an accessible platform for makers to experiment. I recently read about a lorry driver who, drawing on past computing experience, used a Raspberry Pi to enhance his job on the road—a perfect example of how practical lifehacks can enrich everyday tasks.

In this sense, today’s young lifehackers are tomorrow’s innovators, and it’s worth encouraging curiosity and experimentation. I wonder if the same drive exists today as when I was constantly breaking and building things. What are your thoughts, or perhaps your own lifehacking experiences?